The Politics of Hate Speech in Nigerian Elections

Nigeria is a multi-ethnic country with over 200 indigenous languages. Although this diversity is a source of pride, it has also caused rifts rooted in ethnic divides, with some dating back to pre-colonial times. The 1967-70 civil war did not make the case any better. It deepened these divisions, which remain evident during elections. These ethnic divisions permeate not just national politics but also interstate dynamics.

In many instances, political actors have exploited these divides, using hate speech, misinformation, and disinformation as tools to sway public opinion and seize power. While hate speech is regularly discussed, especially in the lead-up to elections, there remains no clear and universally accepted definition of the term in Nigeria. This ambiguity leaves room for personal interpretation and abuse.

Despite several attempts by Nigeria’s legal system to address hate speech and disinformation, implementation of the law remains weak. Section 123 of the 2022 Electoral Act, which targets false publication and defamation of electoral candidates, is a key example. Since its enactment, despite the spread of numerous false claims through social media akin to hate speech, no significant prosecutions have been carried out under the law. This gap between legislation and enforcement continues to allow hate speech to flourish during critical political moments. The 2023 general elections and the recent Edo gubernatorial elections showcased the pervasive use of hate speech to incite ethnic and political divides.

Hate speech weaponized in the Edo elections

The Edo State gubernatorial elections, held on 21 September 2024, highlighted the widespread use of hate speech as a campaign tactic. Monday Okpebholo was declared the winner the following day on 22 September. In addition to the common electoral issues such as ballot box snatching and over-voting, hate speech emerged as a prominent tactic used by political actors throughout the campaign. All three major candidates were subjected to such attacks throughout the campaign.

In the lead-up to the election, the CDD countering disinformation team curated a lexicon of expressions related to the election based on media trends. These expressions were used for social media monitoring through the open-source tool Meltwater.

The team found that tribalism was central in campaign discourse, with hate speech sparking conflict between the Yoruba and Igbo ethnic groups neither of which had a significant stake in the election since Edo state is home to the Binis, Esan, and Afemai ethnic groups. The Labour Party (LP) candidate, Olumide Akpata, was a major target, largely due to his name. Many believed “Olumide” was a Yoruba name rather than an Edo one, and falsely questioned his legibility to run for office in Edo State.

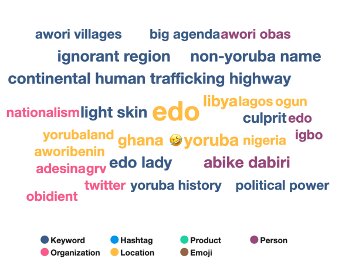

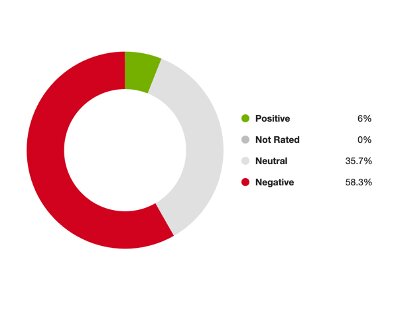

Word trends associated with ‘Tribalism’ highlighted by Meltwater. To the right, the sentiment attached to the trends shows 58.3% negative

Tribalism often manifests in electoral processes, social interactions, and national policies, contributing to marginalization, and even violence among different ethnic groups. This prevailing negative sentiment as indicated on Figure 1 reflects how tribalism continues to undermine national unity and complicate efforts toward inclusive governance and peaceful coexistence. The breakdown of the words choice and associated sentiment highlight the deep-seated division and challenges in Nigeria.

One of the most common insults directed at Monday Okpebholo was “illiterate.” Between September 16 and 22, 2024, there were 318 mentions of this term in relation to the Edo elections, with an average of 45 mentions per day. The use of the term peaked on election day, with 137 tweets using the word ‘illiterate’.

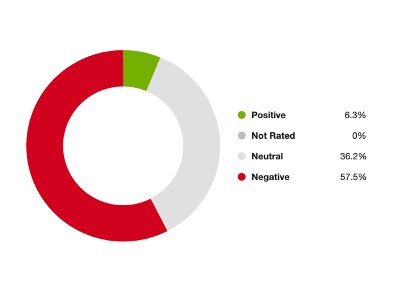

Word trends associated with ‘illiterate’ highlighted by Meltwater. To the right, the sentiment attached to the trends shows 57.5% negativity.

The analysis of word trends associated with “illiterate” in Figure 2 shows that 57.5% of the sentiment surrounding the term is negative. This high rate of negative sentiment indicates the stigma attached to illiteracy in public discourse, reflecting how individuals or groups lacking formal education are often marginalized. The attacks on Okpebholo’s educational qualifications were part of a broader disinformation campaign, which even included the circulation of a deepfaked document falsely presenting him as uneducated. Less than an hour before the election, what seems to be a coordinated campaigned went viral on social media platforms including X, Instagram, and Facebook, falsely claiming that a magistrate court in Abuja had disqualified Okpebholo based on his academic background.

Gendered Hate Speech

Hate speech during the Edo elections was not only ethnically charged but also gendered. Politicians used primitive and misogynistic language to attack one another. A notable example came from former Edo State governor Adams Oshiomhole, who targeted incumbent First Lady Besty Obaseki by calling her “childless.” Oshiomhole remarked, “Here is a woman who has no child. Between him and Obaseki, they have no child; they are childless... People who have love for children go to motherless homes and adopt children. They have not adopted, and they are both in their sixties.” The cultural context of the remark makes it even more harmful as it reinforces misogynistic norms while diverting attention from policy issues. In Nigeria, there is stigma associated with being married and not bearing children, especially for women, who bear the brunt of societal shame and embarrassment. Childlessness can lead to exclusion, with some women being denied participation in activities involving mothers, or children even discouraged from interacting with them, as they are sometimes viewed as bearers of bad luck.

However, Betsy Obaseki was also guilty of spreading disinformation. She falsely claimed that Asue Ighodalo was the only candidate who was married, disregarding the fact that both Okpebholo and Olumide Akpata are married as well. In Nigeria’s sociopolitical context, political leaders are often expected to be married and have a family of their own, as this is seen as a marker of responsibility and stability. Those who are unmarried or childless are frequently subjected to societal shame and may be excluded from key projects or leadership roles, as marriage is associated with a “good reputation.” Additionally, remaining single beyond a certain age is widely frowned upon, further highlighting the entrenched societal expectations.

Both Oshiomole and Obaseki capitalised on already entrenched social expectations to elicit a negative reaction aimed at shaming and bullying their opponents.

Days later, Oshiomhole escalated his attacks on the Obasekis, comparing Governor Obaseki to “an old goat whose children ran away.” This remark followed closely on the heels of his earlier comments about the couple being childless.

Hate Speech in the 2023 General Elections

The ethnic and gender-based attacks seen in the Edo gubernatorial elections echoed the ethnic bigotry that marred the 2023 general elections. Hate speech reached new heights during that period, particularly in Lagos, where the gubernatorial election was defined by ethnic divisions. Political chieftains played key roles in perpetuating these divides, with former Minister of Aviation Femi Fani-Kayode being a prominent figure in pushing an Igbo vs. Yoruba narrative.

The use of ethnic-based hate speech was not limited to Lagos. PDP presidential candidate Atiku Abubakar also contributed to the rising ethnic tensions. Speaking at an Arewa town hall in Kaduna, a region predominantly populated by Hausa and Fulani people, Atiku said the country did not need an Igbo or Yoruba president but rather “someone from the north.” While some may argue that this statement did not directly incite violence, it reinforced the ethnic divides that have long plagued Nigeria. It was an example of the “I did not start the fire, I only gave free fuel” approach to ethnic bigotry in politics.

A Way Forward

A major challenge in addressing hate speech lies in the lack of a universal definition for the concept. The Cambridge Dictionary defines hate speech as “public speech that expresses hate or incites violence against individuals or groups based on race, religion, gender, or sexual orientation.” However, the concept of what qualifies as “hate” or “disparagement” varies widely depending on the context and jurisdiction.

In Nigeria, the proposed 2019 Hate Speech Bill defines hate speech as the use, publication, production, performance, or distribution of any material whether written, visual, or verbal that is threatening, abusive, or insulting. The bill criminalizes such speech if it is intended to incite ethnic hatred or if, under the circumstances, ethnic hatred is likely to be incited. The bill also proposes the establishment of an Independent National Commission for Hate Speech and prescribes life imprisonment for offenders, with the death penalty for cases where hate speech results in the loss of life.

However, this bill was widely interpreted by the public as an attempt to suppress freedom of speech. It lacked clear metrics for determining what constitutes “insulting” or “abusive” speech and did not address the specific issue of gendered disinformation. The bill also failed to specify how to differentiate between legitimate speech and disinformation.

To effectively address the issue of hate speech while protecting freedom of speech, Nigeria must first adopt a clear and universally accepted definition of hate speech. This definition must take into account ethnic, gender, and religious contexts, while also ensuring that the legislation designed to curb hate speech includes provisions for proper implementation. Additionally, the law must ensure that penalties for hate speech do not stifle legitimate free expression but rather target harmful, inciting, or disinformative speech.

While freedom of speech is a fundamental right, it must be balanced with accountability, especially when speech is used to incite division, hatred, or violence. With clearer definitions and more robust enforcement, Nigeria can move towards a legal framework that protects both free speech and the unity of its diverse population.

Chioma Iruke is a countering disinformation specialist at the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD-West Africa)